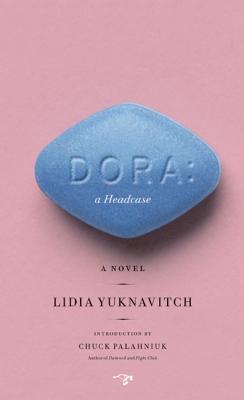

The Reviewed: Dora: A Headcase by Lidia Yuknavitch

The Reviewer: Judy Clement Wall

***

Last year, in a post titled “Writing Brave,” I referenced Lidia Yuknavitch’s memoir The Chronology of Water. I wrote that I loved it “for its determination to look squarely at the wreckage of a truly broken heart and not make it pretty or poetic or simple.” I also said “I was instantly riveted, then shaken, then filled unexpectedly with hope and a very real reluctance to reach the end.”

I just read Yuknavitch’s novel, Dora: a Headcase, and everything I said in my “Writing Brave” post applies. On its cover, Dora is described as a contemporary coming-of-age story, and I guess that’s what it is, but it’s also badass social-sexual-political-psychological commentary. It’s part history, part fantasy, part literary, part thriller-satire-mystery-speculative… well, case study.

Maybe I should start there. Dora is based on a famous Sigmund Freud case study, in which Ida Bauer (a patient to whom he assigned the pseudonym Dora) was diagnosed with hysteria. Ida tells Freud about her dreams and the sexual advances of an adult family friend, and Freud interprets all of it as the manifestation of Dora’s own repressed sexual desire for her father (and the man making the advances, and the man’s wife). All of that happens in Yuknavitch’s updated version too, but in this story, Freud clearly isn’t in charge; 17-year-old Dora is – young, fierce and smarter than all the adults struggling to control her. In both the real story and the book, Dora’s most noticeable symptom is the loss of her voice, and yet she says more without it than all the talking characters do.

Contemporary novels don’t usually begin with introductions, but this one does. The intro is written by Chuck Palahniuk, which is interesting because the unfolding of Dora reminded me of the wild unraveling of Fight Club. Each step the plot takes in the beginning makes sense, each decision abides by the novel’s internal logic, so much so that in the final pages, when the story is careening madly toward its surprising yet somehow inevitable ending, I wondered, “How did we get here?”

And I didn’t care.

Because here’s the thing about Dora. Underneath all the clever re-envisioning (Carl Jung is a made-for-television rock star psychologist) and biting irony (psychological case studies as compelling reality TV), Yuknavitch’s novel has a hungry, searching, beautifully beating heart. It’s the story of a girl learning how to be a fully functioning badass woman in a world that doesn’t really teach us that. It’s about love and friendship and loyalty and the tragic-sweet-tender way that families can get so very fucked up. It’s about the families we’re born into and the ones we choose, and how despite our (sometimes Herculean) attempts to prevent it, both kinds get inside us, both kinds make us who we are.

In the end, I loved Dora: a Headcase: because it’s a smart, ballsy breathless-making book that manages to be both in-your-face and achingly tender at the same time.

Which is what I’ve come to expect from Lidia Yuknavitch.

***

Judy Clement Wall’s short stories and essays have been published in numerous literary journals and websites such as The Rumpus, Lifebyme, Smith Magazine and Beyond The Margins. You can find out more about her and her work at Zebrasounds.net.