This is the latest in Colin Dickey’s The Canny Valley. To go to the column page, please click here.

Somewhere in the distant future, in the derelict remnant of a liberal arts college named the Martha Graham Academy, a feckless student named Jimmy turns out an academic dissertation on the self-help books of the twentieth century. This is Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, and since it’s Atwood, it’s dystopian—a future world in which biotech is king and the study of serious literature has been displaced by the analysis of books like Improve Your Self-Image, The Twelve-Step Plan for Assisted Suicide, and How to Make Friends and Influence People.

Like all dystopian literature, it’s meant as a cautionary tale, but I decided to take Atwood seriously for a moment, and try to study, or at least think about, self-help as a genre. After all, in many ways the future is already here. The rhetoric and style of self-help has infiltrated the literary landscape in more ways than we’re ready to admit—it’s shape-shifting and mutable and it’s filling holes in the writing world in odd ways. The goal of this column being to explore and play with different kinds of genres and different kinds of possibility, something as risible and easily dismissed as self-help seemed worth investigating.

***

Self-help, as a genre and as a term, begins with Samuel Smiles’ book, Self-Help, self-published (naturally) in 1859 four years after being rejected by Routledge. Smiles was not the only one at the time exhorting his fellow men to better themselves: the first half of the nineteenth century were awash with various movements that promoted panaceas to cure all of society’s ills: phrenologists, teetotalers, vegetarians, hydrotherapy advocates, anti-lacing societies (against corsets: “Natural waists, or no wives!”), and on and on—all promising simple, quick fixes that would lead to utopian harmony.

Smiles rejected all of that; the key to success, he argues in Self-Help, is knowledge and hard-work. “Men must necessarily be the active agents of their own well-being and well-doing,” he writes, “and that, however much the wise and the good may owe to others, they themselves must in the very nature of things be their own best helpers.” Reading more like a school-marm than a self-help guru, Smiles advises us that the

greatest results in life are usually attained by simple means, and the exercise of ordinary qualities. The common life of every day, with its cares, necessities, and duties, affords ample opportunity for acquiring experience of the best kind; and its most beaten paths provide the true worker with abundant scope for effort and room for self-improvement. The road of human welfare lies along the old highway of steadfast well-doing; and they who are the most persistent, and work in the truest spirit, will usually be the most successful.

What perseveres about Smiles’ book, some 150 years later, is the drive to find a language that reaches through the page and convinces the reader to be better than s/he currently is. But if Smiles’ book launched a genre, the genre Self-Help launched is fundamentally antithetical to its own founding. The subsequent history of the self-help genre has been largely bent on proving Smiles wrong: positive thinking does have power, riches can be got quick, highly successful people do have habits. There is a Secret.

Self-help, properly speaking, is not a genre but an affect, a re-packaging of the same sentiment, altered slightly through repetition but largely unchanged. And it is this sentiment which has lately left the confines of the self-help section and begun infiltrating genres previously assumed to have more seriousness and merit. One finds it in pop neuroscience, in writers like Malcolm Gladwell and Jonah Lehrer, and in Naomi Wolf’s recent Vagina: A Biography. And one finds it in memoir, in Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love and James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces.

The high-profile world of pop neuroscience so thoroughly mirrors the junk science and quick-fix promise of phrenology that it’s almost not worth pointing out, save for the fact that gurus like Gladwell are still peddling snake-oil on the TED circuit for tens of thousands of dollars per lecture. As Isaac Chotiner summed it up in his review of Jonah Lehrer’s latest book:

Imagine is really a pop-science book, which these days usually means that it is an exercise in laboratory-approved self-help. Like Malcolm Gladwell and David Brooks, Lehrer writes self-help for people who would be embarrassed to be seen reading it. For this reason, their chestnuts must be roasted in “studies” and given a scientific gloss. The surrender to brain science is particularly zeitgeisty. Their sponging off science is what gives these writers the authority that their readers impute to them, and makes their simplicities seem very weighty.

Latent behind Lehrer and Gladwell is this same self-help motivation: this simple thing can change your life for the better. Lehrer’s book on creativity, Imagine, ends with this promise:

For the first time, we can see the source of imagination, that massive network of electrical cells that lets us constantly form new connections between old ideas…. Thanks to modern science, we’ve been blessed with an unprecedented creative advantage, a meta-idea that we can apply at the individual level. For the first time in human history, it’s possible to learn how imagination actually works.

We are not far in these lines from Atwood, and the idea that human imagination and spirit has finally been decoded and can be maximized for earning potential. One tries to imagine the ramifications of Lehrer’s nonsensical claim that science has given us “an unprecedented creative advantage”—over what? And what will it mean to be “more creative”? More books published? More “Like a Rolling Stones” written? More widgets manufactured? The mind boggles.

But this is the foundation of self-help, after all: unlock the secrets that make me better, and then tell me what to do. Give me actionable intelligence, make me more creative, increase the percentage of solutions I’m able to devise. Give me a plan because I’m incapable of making my own; give me a plan because mine isn’t working.

This impulse to boil down the messy complexity of the world into simple statements, slogans and clichés, lies behind the majority of memoirs that appropriate this same self-help mold—particularly and most obviously, the ersatz and disgraced memoir/novel, A Million Little Pieces by James Frey. Frey’s rhetorical trick, other than the fictive sensationalism that he was later taken to task by Oprah for, is a repeated tic in which any semi-complicated notion or philosophy is always reduced, at the end of the paragraph, to a stock cliché. His reading and paraphrasing of the Tao Te Ching takes up several pages, then ends on this note: “Although I am no expert on this or anything related to this or anything at all except being a fuck-up, I seem to understand what this book this weird beautiful enlightened little book is saying to me. Live and let live, do not judge, take life as it comes and deal with it, everything will be okay.” Likewise, James’ friend Leonard offers a heartfelt speech on misery and triumph that finishes with: “Be smart, be strong, be proud, live honorably and with dignity, and just hold on.”

Live and let live. Do not judge. Live honorably and with dignity. Hold on. Self-help wants nothing more to simplify the world down to these clichés. It’s not a coincidence, I think, that both Frey and Lehrer were caught in scandals regarding fabrications—Frey of life experience, Lehrer of source quotes. When you cannot reduce the world to slogans, you invent the world and you invent data so that you can. What both of these scandals suggest is that, taken to its extreme, the job of self-help is strangely impossible. Life is too messy, and attempts to reduce it to the firm and unquestionable lesson or cliché requires doctoring the evidence.

***

But the road goes both ways: if self-help has infected the literary, the literary has also recently begun to infect self-help, in ways that are infinitely more promising than Lehrer and Frey. At the other end of this spectrum is Cheryl Strayed’s advice column for The Rumpus, Dear Sugar, which was recently collected and published as Tiny Beautiful Things. Strayed, like Frey, deals in—if not clichés, then slogans. “Trust yourself,” she writes in one column, “It’s Sugar’s golden rule. Trusting yourself means living out what you already know to be true.” Another 2,000 word post features the maxim: “Write like a motherfucker”—helpfully available now on mugs and t-shirts.

What’s interesting about Strayed’s column, though, is that these slogans and maxims are, as often as not, near the beginning of the column rather than the end. The best posts dispense advice almost perfunctorily, before moving into long personal essays—essays that at times can seem like digressions. “Several months after my mother died I found a glass jar of stones tucked in the far reaches of her bedroom closet,” begins one answer.

I was moving her things out of the house I’d thought of as home, but that no longer was. It was a devastating process—more brutal in its ruthless clarity than anything I’ve ever experienced or hope to again—but when I had that jar of rocks in my hands I felt a kind of elation I cannot describe in any other way except to say that in the cold clunk of its weight I felt ever so fleetingly as if I were holding my mother.

At times like this, the original letter writer almost seems beside the point; Steve Almond gets it right in his introduction when he describes Dear Sugar as not a “column” but an “ad hoc memoir.”

Sometimes, these stories loop back to the matter at hand, but sometimes they don’t. After confessing to searching for objects that would give her her mother back “in some indefinable and figurative way that would make it okay for me to live the rest of my life without her,” Strayed goes on to conclude “I didn’t find it in those stones…in spite of my hopes on that sad day. It wasn’t anywhere, in anything, and it never would be.” These personal stories often as not don’t resolve, and don’t offer a moral beyond pain and the absence of tidy redemption. These essays often only masquerade as self-help. She is at her best when she moves beyond the central thrust of self-help into messiness and ambiguity; as a reader, I’m most annoyed when these essays return to the lesson. It’s here that the somewhat artificial distance between seeker and sage reasserts itself, and why I find myself tending to disagree with Almond’s assertion that these essays represent “radical empathy.”

Radical empathy suggests to me not these fairly successful advice columns, but the disastrous advice columnist from Nathaniel West’s Miss Lonelyhearts. West’s eponymous columnist is so radically empathetic he cannot write; he is overwhelmed by the endless drawer of letters, “all of them alike, stamped from the dough of suffering with a heart-shaped cookie knife.” He is rendered speechless; he cannot get beyond the first, empty sentence of his never-written column: “Life is worth while, for it is full of dreams and peace, gentleness and ecstasy, and faith that burns like a clear white flame on a grim dark altar.” Not unlike Dear Sugar, Miss Lonelyhearts’ advice column began as a joke, though here the joke turns sour; unlike his editor Shrike, he can’t distance himself from the morass of human suffering, cannot laugh it off with bromides and lessons and clichés. It’s no way to be; West’s novel is a cynic’s cautionary tale—if you truly open yourself to other humans, you’ll drown. In radical empathy lies death.

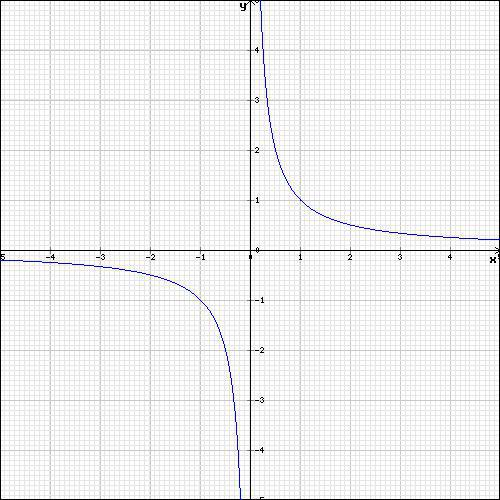

On one end of the self-help spectrum, then, is the impossible reduction of the world into slogans that can only be carried off through sleight-of-hand, invention, and duplicity. At the other end is Miss Lonelyhearts’ radical empathy, with its attendant speechlessness, nihilism, and self-destruction. The genre of self-help lies on the curve that years towards these two separate asymptotes—it can approach either pole but never fully get there without imploding somehow. The world is too messy, empathy is too messy.

Contrary to Atwood’s skepticism, this is perhaps what makes self-help such a potentially fascinating genre, and leaves me wondering if there’s room for more writers like Strayed to attempt it. It seems that there’s still unexplored possibilities—like an unstable isotope, it exists between two impossible poles, quivering with power somewhere in between.

More of Colin Dickey’s The Canny Valley at Used Furniture.

Loved this. I’ve had an essay brewing for a while now on finding the line between being vulnerable and open and being a complete nihilist that it’s definitely time to revisit. Coincidentally, just started Miss Lonelyhearts last night. Loved that line about the cookie knife.