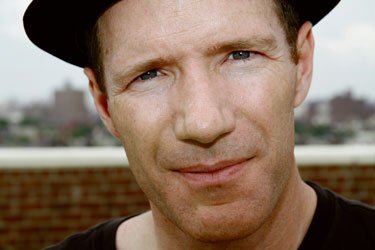

Rick Moody is the author of four novels: Garden State, The Ice Storm, Purple America, and The Diviners, as well as three collections of short fiction, The Ring of Brightest Angels Around Heaven, Demonology, and Right Livelihoods. His first novel, Garden State, won the Pushcart Editor’s Choice award, and his memoir, The Black Veil, won the PEN/Martha Albrand award for the Art of the Memoir. Moody’s 1994 novel, The Ice Storm, a bestseller, was made into a feature film of the same name and was directed by Ang Lee. His passion for writing is equally matched by his passion for music. A founding member of The Wingdale Community Singers, Rick also writes about music as a regular contributor to The Rumpus. More at http://www.rickmoodybooks.com/.

***

UF Review: Your most recent novel, The Four Fingers of Death, seems like it was a pretty ambitious undertaking. What inspired you to pursue the idea? How did the novel start? What sparked its creation?

Moody: I watched a lot of monster movies as a kid. In fact, in the period after my parents divorced, which was in 1970 or so, the one thing that I did reliably no matter the address was watch horror movies on Saturday nights. My brother and my sister were sort of the same. This was a bonding experience of some kind for us. The horror of The Blob or I Was a Teenage Werewolf was less horrifying than domestic horror. Or: by surviving the monster movies we were indemnifying ourselves against further domestic trauma. (This didn’t turn out to be true, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t a reasonable hypothesis at the time.) Meanwhile, I was also beginning to read more serious work, if my by serious work you mean not The Hardy Boys. Narrative as a way of life was beginning to figure in me, to call to me, narratives both sacred and profane. When I set out to write this book, I wanted to suggest that period. Not only the horror movies (and The Crawling Hand, which is the basis for the book, was one I watched back when), but also the science fiction and the popular countercultural fiction (Vonnegut, Brautigan, Tom Robbins, Joseph Heller) that I first encountered in the early and mid-seventies. I wanted to get back to the kind of work that made me a reader in the first place.

UF Review: There’s a theory knocking around out there (though I can’t recall my source) that we’re now not only living in a post-9/11 era, but in an era in which our literature is a response to 9/11 and its implications. Do you buy that? If so, is your current work influenced by our current state of affairs? What influences your fiction?

Moody: I think I already kind of wrote not one but two books responding to the post-9/11 political atmosphere, namely The Diviners and Right Livelihoods. I sort of felt with Four Fingers that I might include less overt politicizing. Sometimes I think the politically tendentious can be aesthetically heavy-handed, you know? I’m not sure I buy the theory, therefore, the one you are sketching out, except to say that it’s inevitable that people are going to think about 9/11 some of the time. Why wouldn’t they? But I’m a bit suspicious of unitary influences imputed to American literature, because American literature is so various. There’s no one literature for our country. It’s too culturally diverse for that. Politics are important to me as a writer, the political landscape figures in what I do, but I would say that music and art do as well. And the history of the novel form. Probably nothing influences me more than the history of the novel form.

UF Review: For you, what does fiction accomplish?

Moody: The explication of consciousness.

UF Review: You’re also a pretty avid music fan. Are the accomplishments of fiction the same as those of music and lyricism? Can one genre perform better than the other? Why or why not?

Moody: No artistic medium is quite like any other, it seems to me, in terms of its effects. Painting is about light and color. It can have drama and narrative, but more importantly it’s really about light and color. Sculpture is about space and plasticity. You could make the argument that cinema is synthetic, in that it makes use of so much else (writing, music, visual art), but even there I think you have a very specific formal history, with very unique interests and strengths, all of these different from the media that it, cinema, engulfs. So I think, according to a philosophy of difference, that music and literature are very, very different. Doesn’t make sense to compare them, really, nor to force them to compete. I use each for a different purpose, in my own life and work. I mean, I am probably an okay writer of lyrics because I am already a person who is interested in the words, in the materiality of literature, but still: with three verses and a bridge and chorus, there isn’t much room in a song for lengthy development. Nor can you get into a narrator’s head terribly well, although Randy Newman does it sometimes, as does Bob Dylan, or David Bowie. Mostly, I play music because I can do it with other people, instead of having to be by myself all the time. The collaboration is very satisfying. What I write songs about has something to do with the circumstances in which I play those songs.

UF Review: You seem to be drawn to music that’s independently produced, the kind that frequently flies under the radar. What draws you to indie music? The raw authenticity? The creativity? The earnestness?

Moody: The records produced by the record business these days do not inspire. There are rare exceptions, such as the Nonesuch label, or some distributed “semi-indie” labels like Matador. Or ECM. But the record labels, in general, are running scared. As with American literature, I don’t believe there is one unifying sound to the music that is produced now. So I can’t say that I write about “indie” because I think it means just one thing to do so. I simply like a lot of obscure stuff, am drawn to neglected music, and this tends to be on smaller labels, or is self-released, or is unreleased, or what have you. Also: there are a lot of people writing about the bestsellers, anyway. This is not to say that there are not “popular” artists worthy of attention. My collection of essays on music, coming out in 2012, deals with some rather well-known people: Pete Townshend, Wilco, The Magnetic Fields, The Pogues, etc. But these days, somehow, I fall more easily, emotionally, into rarer things.

UF Review: On a similar note, what do you enjoy reading? Who are some of your favorite authors and writers? Any favorite books?

Moody: It depends what day you ask — favorite books. Here’s today’s list, different from tomorrow’s list: The Recognitions, To the Lighthouse, Rings of Saturn, Murphy, The Crying of Lot 49, Break It Down, White Noise, Moby Dick, The White Album, anything by Montaigne, or Roland Barthes, or stories of Kafka, Bruno Schulz, etc.

UF Review: The Black Veil is pretty striking for several reasons, particularly its honesty. How easy or difficult was it to really examine yourself with such an intimate lens? What was it like to release yourself, essentially, to the world?

Moody: The Black Veil was very difficult to write, I would say, probably the most difficult book I have ever written, but its compositional complexities were nothing when compared to publishing it. Publishing it was a total heartbreaker, and not just because of some less felicitous reviews. Publication was a heartbreaker because wherever I went I encountered people who were really sad, and, in many cases, clinically depressed, some of them seriously so, who wanted to talk about their experience. I do not regret writing what I wrote, and I am honored when what I have written strikes people enough that they want to tell me about their own lives, but it’s really emotionally taxing, in truth, especially when, essentially, I am a shy and rather guarded person. I want to have an audience and to interact with my audience, of course, but I am also shaken deeply, now and then, by the recognition that what I do has, in some cases, a real impact. This experience, The Black Veil experience, was therefore demanding, and I would be unlikely to repeat it any time soon. Moreover, I realized that as a memoirist I lack some crucial kinds of exhibitionism that animate others who work in this field. I don’t actually believe you can tell the unvarnished truth about your own life, for example. There’s always some massaging and shaping of the truth going on.

UF Review: Also striking in your work, overall, I think, are your narrators. Are your narrative voices innate? Out of all you’ve read, are there any authors in particular that are especially adept in capturing the idea of narration?

Moody: In order to answer this in the spirit it’s asked, I would have to understand what’s striking about my narrators, and they don’t seem terribly striking to me. Just accurate, I guess, or human. I think maybe what you are saying is where do these voices come from? And I suppose I would say that they have their origin in the way Jack Hawkes, my instructor at Brown (during my undergrad years), stressed voice. I think with the eccentricities of linguistic usage you get a sense of a person as much as you do by describing their appearance. Voice and language, therefore, are the building blocks of character. So I have to get their voices first. Many of these voices are not so far from my own, or they are all contained within me. Montese Crandall, in Four Fingers, e.g., is just a hyperbolic version of myself, pushed into the register of the comic. It is not too difficult to come up with that voice.

UF Review: The Ice Storm revolves around life in Connecticut, your childhood stomping grounds. Besides location, are there echoes of your own life in your fiction? Does personal experience influence your work? That is to say, does writing inform your life or does your life inform your writing?

Moody: The movement in and out of autobiography is something dialectical for me. I am always somewhere on a continuum between the completely imaginary and the completely accurate. Of course, there can be neither. This is sort of like the false dichotomy of capitalism vs. communism. There is no real libertarian capitalism, never will be, and neither is there perfect communism, no planned economy that has no capitalist incentives at all. The political rhetoric that suggests that these things exist is just an attempt to score points with the electorate. In the same way: I am always moving toward or away from personal experience. The Black Veil was very close to it. The Four Fingers of Death is far away from it, indeed. This is how I work, and I bet it’s how a lot of other writers work too.

UF Review: How do you approach the two genres, fiction and nonfiction? For you, what are some similarities between the two? What are some differences? In writing, is your overall process the same?

Moody: I approached The Black Veil structurally exactly as if it were a novel. The formal ideas were just the next step from Purple America, the novel that came before it. But there was still this gnawing responsibility to tell the truth all the time, while writing The Black Veil, and frankly that just got really tedious. Which is why The Diviners basically wrote itself. That novel just poured out of me. Because I was so happy just to go wherever the invention led for a change. Again: language doesn’t know what genre it is in. It only knows that it is language and that it proceeds from the self, from the narrator of tongues. But once the language cools toward absolute zero we can begin to plot it somewhere between factual and invented, at least theoretically, and that’s where all the problems start. If there were no bookstores, there would be much less talk of genre, and literature would be much more liberated.

UF Review: What does your revision process look like?

Moody: It’s really long. And I am much improved during it.

UF Review: How do you know when you’re really done with something? Whether it’s a short story, a novel, or a piece of nonfiction, how do you know when a work is totally exhausted? I mean that in a good way, of course.

Moody: A work is never exhausted. I just stop. Sometimes I stop because I am down to microcosmetics (changing that to which and back again), sometimes I stop because the deadline is here. But I never stop fixing things. On Right Livelihoods, e.g., I was changing things in the galleys up to the very last hour I could change things. They said I had to stop on a certain day by 3:00 p.m. And if I anthologize any of those stories, from that book, I will likely change them yet again. Over the life of a piece you usually alter it less radically, as you go on, and that’s how you know it’s getting better. But there’s no done. There’s no complete. There’s no exhaustion. There are only provisional versions of texts for particular purposes.

UF Review: If you were to talk to someone who didn’t know what music was, had never even heard of the stuff, what song would you play to make him or her understand?

Moody: Tuvan throat singing, African clicking languages, that recording of those postal workers in Uganda making up songs while they use the hand-stamper to cancel the stamps, a recording of a Japanese girl listening to Jesus Christ Superstar on headphones and singing the English words phonetically, Bach’s “Air on a G String,” a recording with contact mics of beetles boring into Ponderosa Pine, all recordings of birds, a recording of the sound of someone typing a resignation letter and crying occasionally, Doo-Wop harmonies, plainsong, the sounds of trains rumbling through the towns of the Southwest, Skip James’s “Hard Time Killing Floor Blues,” anything by La Monte Young, Indonesian guitars, that album that Colin Turnbull did of the pygmies, song-poem anthologies, people singing in the shower believing they are unheard, Sun Ra, that recording of First Nations people singing about Mighty Mouse, the wind on the prairie, dogs howling at sirens, Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, Meredith Monk, the sound of your heartbeat while you are standing next to a glacier in Iceland, children laughing, Terry Riley, the sound of a parakeet imitating death metal, did I already include that one?

More interviews at Used Furniture.

Great interview. Music is indeed its own mystery, separate from literature. Adjacent, maybe, but separate.

I am so happy to read this. This is the kind of manual that needs to be given and not the random misinformation that is at the other blogs. Appreciate your sharing this best doc.

Great, insightful read.

This is a great interview.

It’s hard not to think about voice in terms of grace rather than as something truly voluntary. Is that an abdication of responsibility? I don’t think it means that you can’t put effort into making the most of it, recognizing it when it comes upon you…but I can’t shake that sense. Maybe it’s different for everyone.

I would love to hear the Jesus Christ Superstar tape.