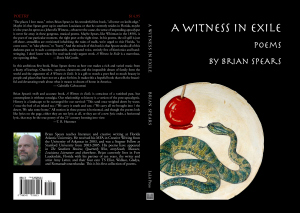

Brian Spears is the Poetry Editor of The Rumpus, as well as a published poet. He is also an Instructor of English at Florida Atlantic University, where he teaches Creative Writing, Literature, and Composition. His first book, A Witness in Exile, is available from Louisiana Literature Press, and also from his website.

***

UF Review: Could you talk a little about yourself? Who are you as a person?

Spears: It’s just a coincidence, I suppose, that I’m teaching “Theme for English B” by Langston Hughes tomorrow morning, given that I’m tempted to list things like my age and where I’ve lived and who I’m related to (and not related to). I could define myself by what I’m not anymore — I’m not a Jehovah’s Witness anymore, and that’s a theme in the book — but that only gets you so far.

UF Review: Wow, how did it feel to renounce that lifestyle? Was it hard to pick up a new identity?

Spears: Like any life-changing moment, really hard and really freeing. The Witnesses practice shunning members who have left the church — their term is “disfellowshipping” — but what it means in practical terms is that no member of the church, not even family members, is supposed to have anything to do with you. The result for me was that I lost not only most of the long-term friends I’d ever had, but my relationship with my parents as well. We haven’t had a real relationship since 1996.

And finding the new identity was also tough. Lots of growing pains, you know? It was like I had a second adolescence, complete with all the awkwardness that entails. A little less acne this time around, but a lot more substance abuse. Being in college helped, because I had a built-in social network to help me adjust, but it was still tough.

UF Review: So you’ve struggled with the notion of self here in the world. Is your “self” present in what you’ve written?

Spears: Saying I’m in the book is a bit flip, and not precisely true either, because we’re all liars to some extent when we’re performing. We lie to ourselves just to get through the day sometimes.

UF Review: I’m struck by your use of the word ‘performing.’ Are you saying writing is a performance? How so?

Spears: Well, it is for me. I want people to read what I write. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t try to publish it, after all. I think when some writers say they write without the audience in mind, what they’re trying to say is that they’re more concerned with their personal vision than they are with commercial success, and I agree with that. But I think we’re fooling ourselves as writers if we claim that we don’t care what our audience thinks. Of course we do. Otherwise we’d stuff our notebooks in the closet when we filled them up instead of showing their contents to the world.

UF Review: When did you realize you loved poetry?

Spears: I fell in love with poetry, like I suspect most poets do, in high school, that time in my life when I was first really starting to get a desire to express myself as an individual. I’d written poems for class assignments and such when I was even younger, but the first time I started to do it on my own was junior year.

I put it down for a long time until I went to college when I was 26. About 8 weeks into my first semester in school, I left the church I’d attended all my life, and my wife and I split up after six years of marriage. I needed to vent, and I returned to poetry.

UF Review: When you needed to vent, did you go to poetry immediately? I guess what I’m asking is, why poetry? What can poetry do that other forms can’t?

Spears: I suppose I could have vented in fiction, or in memoir, or in song, but those weren’t my genres. I’d never felt comfortable writing stories, even when I was first trying them on in high school. I was a poet in my bones, I guess. Even to this day, I don’t think of myself as anything else. Blogger, maybe. I don’t have the patience to work with prose, I think. Too many words. Though I’ll beat a poem to death trying to get the words right.

UF Review: I love that phrase, “I was a poet in my bones.” It seems like leading a life of poetry was inevitable, but when did you know you wanted to pursue it?

Spears: I didn’t start studying it seriously until a 5-credit hour Calculus class kicked me in the junk 3 times (I don’t get hints easily) and I changed my major from Chemistry to English, but the love was always there. The first book I ever bought with money I’d earned was E. E. Cummings’ A Selection of Poems. I still have it to this day, 25 years later.

UF Review: Besides Cummings, do you have other touchstone poets? Is it important to have other writers to look to?

Spears: I wouldn’t even say Cummings is a touchstone anymore. He got me started, and I wrote like him for a while, but I moved on. I still love to read his work, but mostly because it brings me back to those earliest days of discovery, not because of the work itself.

I read so widely today because of my work at The Rumpus that it’s hard to lock in on a single poet or even a handful of them. Philip Larkin, maybe? And James Merrill definitely. And while I have very little time to read older work these days, that’s okay because I’m in love with a lot of contemporary poets, even established ones I’m just discovering — Jena Osman and Kirsten Kaschock were my last two Rumpus Poetry Book Club selections, and they blew my mind. Sandra Beasley, Douglas Kearney, Gabrielle Calvocoressi, Barbara Jane Reyes had killer books come out in the last year or so. I’ve been a fan of T.R. Hummer for a while now, as well as W.S. DiPiero, who was one of my teachers at Stanford.

I don’t know that I look to other writers so much as I’m just in awe of them. I tend to read people who do what I don’t, not because I want to ape them, but because I just dig the difference. I think if I read people who were doing what I do, I’d be too self-conscious to ever write again, and that might kill me. I’m sure if you asked five other poets, you’d get seven different answers to this question. Maybe twenty-two.

UF Review: The Rumpus is doing some pretty amazing things. The Book Club in particular, I think, is fantastic. How did you become involved with The Rumpus?

Spears: I met Stephen Elliott when I was at Stanford as a Stegner Fellow. He invited me, out of the blue, to do a reading with him at the Stanford Bookstore to promote Looking Forward to It, a book about the 2004 Democratic party primaries. It was covered by BookTV, which is, to this date, my only appearance on national television. I actually bought the DVD from C-SPAN.

When he started The Rumpus, he originally asked me to do a weekly column. The details were all still a little hazy, but I started Poetic Lives Online, and then after the Presidential Inauguration in 2009, when I wrote a piece about Elizabeth Alexander’s “Praise Song for the Day,” he offered me the editor’s gig. I became the Saturday editor not long after that as a way to increase our weekend updates.

UF Review: It seems like your involvement has helped you grow a reader, so has being affiliated with that community helped you as a writer, too?

Spears: Oh sure. I think any time you expand your reading horizons, you open yourself up to new possibilities in your own work. I doubt I would have even imagined the project I did last year without having been a part of The Rumpus. The world of poetry is so big and varied that it’s easy to read poetry all the time and never leave your comfort zone. That was my situation before The Rumpus. When I expanded my reading universe, I expanded my awareness of what was possible.

UF Review: You’ve recently released your debut book, A Witness In Exile. Could you talk a little about it? How would you describe the book? How did you decide which of your poems belonged in the collection?

Spears: I suspect the book is, as most first books are, a little uneven. I’ll leave it to the readers to figure out which ones are the high points. When I finished my MFA in 2003, I thought my thesis would be my first book. 7 years later, I’d be surprised if a single poem from the thesis is in there. I’ll admit I haven’t checked. New poems get written; old poems get discarded.

But it’s a mixture of new and old. Some of those poems date back to my time at Stanford — 2003 to 2005 — and some were written last year. And because of that, there’s a swing in styles and subject matter. The poems about being a Jehovah’s Witness are mostly older, though not all.

I depended on good readers — Amy Letter, my long-time partner primarily — to tell me when to keep or when to drop a poem from the manuscript. Sometimes, when I was in the final stages of preparing the book, I just read a poem, decided I didn’t like it anymore, and cut it. That’s what happened to the title poem, for example. But I kept the title.

UF Review: Is it easy for you, then, to discard a poem after you’ve written it? Or is it hard to render your work useless, at least for the moment? Someone once told me writing is like giving blood, it hurts to get rid of it but more always comes. So is that process of sifting through your material just necessary?

Spears: Easy? Depends on the poem. Sometimes I’ll look at an old copy of my manuscript and think, “well of course this didn’t win a contest — half of these poems are crap.” And then I remember that when you look at Seamus Heaney’s Opened Ground, his first selected, and you see how little made it out of Death of a Naturalist, well I don’t feel so badly about leaving some behind.

But there are some poems that I’ve written that I know in my bones are good, even if no one else does, and those are hard to cut. Sometimes you have to trust other people.

UF Review: Have you always wanted to produce a book?

Spears: I remember a conversation with some friends in high school where we were talking about life ambitions, and I said that I wanted to publish a book of poems, and that it didn’t matter if it was a hit (a nod to how ignorant we were of poetry’s popularity) — that if only a handful of people liked it, that would be enough. And then I did absolutely nothing about it for 15 years or so.

I started thinking about a book again when I was at Stanford as a Stegner Fellow and some of the other fellows were submitting to contests. One person at Arkansas, Tony Tost, had won the Whitman the same year I won the Stegner, and prior to that I hadn’t really thought about it at all. I hadn’t published much at all up till then, so a book seemed a million miles away. And it turned out, it was, if 7 years equals a million miles.

UF Review: So when did you realize you had one on your hands?

Spears: I actually thought I had a manuscript a long time ago, but none of the judges I sent it to thought so, and they were who mattered at the time. I approached Jack Bedell at Louisiana Literature Press with the idea of doing a book a couple of years ago, and he’d been supportive of me since I’d been in his classes as an undergraduate. We dodged a lot of bad economic times and managed to get it out, though there’s little budget for anything other than the actual printing. That’s the world of university presses right now — those that aren’t closing are cutting way back.

UF Review: For you, then, what constitutes success? Are you worried about such a thing?

Spears: Can’t say I’m worried about success because I don’t really know what constitutes success in the poetry world. Book sales? Fellowships? Being invited to read or interviewed? Having people request your work rather than having to send it out cold? I don’t ever want to think that what I’m doing is automatic, or that I can’t fail. Too many once-great poets (no names here) have let their work go stale, and I wonder if it’s because no editor will tell them “this sucks — I don’t want it.” I don’t know if I’ll ever be a great poet, but whatever I am, I don’t want to be a guy who writes the same poem over and over again, no matter how well I write it.

I loved reading this interview — it felt like being part of a great, inspiring conversation. Congratulations to Brian on his book, looking forward to reading.