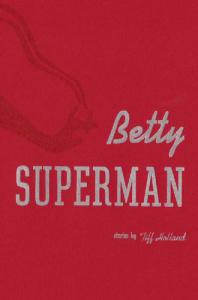

The Reviewed: Betty Superman by Tiff Holland

The Reviewer: Chris Vola

***

Some familial bonds can be impossible to sever, regardless of how inextricably fraught with the rust of pain and discontent the individual links may seem. The 10 connected stories in Tiff Holland’s Betty Superman painstakingly examine the tumultuous, occasionally hilarious and wrenchingly memorable relationship between a mother and daughter thrust together by the brutal stings that life tends to deposit and a need to remain together that neither of the women can completely articulate. A brilliantly detailed portrait of the lifelong and complex intersection of two lives and the vitally intriguing refuse that gets thrown out along the ride.

The book begins with the unnamed narrator diligently recounting the minutiae of her unconventional childhood and early adulthood living with her domineering and mentally imbalanced mother, who sometimes refers to herself as Betty. The clash of personalities is monumental. While the narrator is introverted, level-headed, content to quietly immerse herself in a book, Betty is possessed of attention-seeking gregariousness that flirts with the vulgar and mocks the concept of personal space. She insists on invading her daughter’s room at all hours blasting music on a stereo that isn’t hers and dancing around “like some harlot,” alienating her husband, later boyfriends, and her daughter’s friends, whom she intermittently refers to as “losers, lesbians, perverts.” Her narcissistic mania persists to the point where, bleeding profusely after being bludgeoned in the head by a glass of juice, she can’t help but belt along joyously to the car radio on the way to the hospital, ostensibly to irk her daughter, but mostly she is convinced she has the voice of a female Sinatra. Instead of breaking free from unstable Betty, the narrator, amidst a series of disappointments that include a failed marriage, finds herself still linked to her aging mother, working with her at a beauty shop and later as her driver and some-time caretaker when Betty is reduced to an ornery asthmatic who survives on McDonald’s coffee and Walgreens candy bars. After a serious stroke leaves her daughter frail and devoid of large tracts of her memory, Betty transforms from agitator to grudgingly indispensible. She is the sole connection to a family and personal history that, though often seedy, allows the narrator to rediscover and come to terms with aspects of her own identity, and through the mutual prism of degenerating health, to cement a symbiotic mother-daughter understanding that is both surprising and endearing.

This fictional mini-biopic of sorts benefits greatly from Holland’s ability to vividly extract pitch-perfect observations of truth and nuance from the smallest of details. The descriptions of Betty – her “missile-silo brassieres,” her leaving wilting flowers near her daughter’s bed as a statement of dislike toward the “queery” man who will become her first husband, how she sucks on her oxygen mask and “inhaled as if she were taking a hit” – serve to illuminate the foibles of a ceaselessly fascinating and unique character and reinforce the tongue-in-cheek/hand-on-shaking-forehead opinion the narrator has of her mother. Many of the book’s moments of quiet surveillance also illustrate a beautiful, pervasive sadness, small seedlings growing from cracks in the hard spiritual wreckage, the timid transvestites who come to the beauty shop after-hours and are at most at peace “tottering in circles between the dryers and the styling chairs, trying in that small space to learn how to fly.” But when it comes to the narrator’s personal history, what Holland leaves out is often more important. Very little is brought to light about the narrator’s two husbands, her job (a writing instructor), or her young daughter, Lauren, who seems to drift on the periphery. There are only the brief mentions of a MedicAlert bracelet, how the lights in Walgreens are excruciatingly disorienting and make it difficult for her to walk, how when dining at Cracker Barrel, she always orders the same meal because “it’s getting too hard to actually read the menu and everything here tastes the same.” The stroke-induced amnesia makes the trips with Betty to fast food restaurants, to sell old jewelry, to simply pump the gas, into opportunities to rehash forgotten events, people, and emotions, to not simply recreate an identity but to forge a new one, epitaphs to a soul that could not have otherwise existed. The narrator’s intense and necessary focus on her mother’s past and present is the most glaring and arresting evidence of her own loss of self.

Betty Superman’s best quality is how, in only 32 pages, the book is able to so fully mine the psychologies of two characters with a scope and depth that is novel-length in stature, a rarity in fiction of this length. We know the women in these stories, have seen them ahead of us in the drive-thru line, in untold yards of suburban squalor, wondered and guessed (maybe correctly) at the dark histories hidden underneath the perm and inside the faded purses. It could be that we offered them a tissue or prayed for them in the snacks aisle of a hospital-lit mega-mart, but one thing is certain, they are here. And though it is usually callow and foolish to thrust a fiction writer’s biography upon her work, Holland is in fact a stroke survivor and a professor of writing in Texas, the stories’ ubiquitous setting. One must assume that, regardless of any superficial plot-based similarities, the author has spent an inordinate amount of time at what Faulkner calls “trotting along behind” her characters, soaking up their damaged essences and delicately (and sometimes startlingly)splattering them through the pages. It is a mess well worth making, and reading.

***

Chris Vola‘s fiction, poetry, and reviews have appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, The Rumpus, Verse, Blood Lotus, Staccato Fiction, and elsewhere. He blogs and starves in Manhattan.

More reviews at Used Furniture.