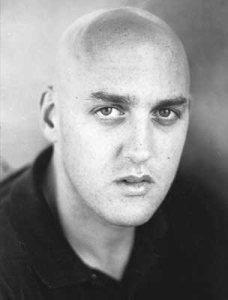

Ben Marcus is the author of Notable American Women, The Father Costume, and The Age of Wire and String, and his forthcoming novel, The Flame Alphabet. His writing has appeared in Harper’s, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The Believer, The New York Times, Salon, McSweeney’s, Time, Conjunctions and Tin House. He is the editor of The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories, and for several years he was the fiction editor of Fence. He has received Whiting Writers Award, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in fiction, and three Pushcart Prizes. You can find him here.

***

UFR: First, do you consider yourself a writer? For you, what does that term mean, exactly?

Ben Marcus: This is what I consider myself:

UFR: When you write do you do so with an eye towards eventual publishing, or do you produce work first and then take me up that concern? In other words, do you write with any sort of audience in mind?

Marcus: I write to an audience I have internalized. It both hates and loves me, but mostly it is suspicious in the extreme of everything I do. It’s an invented audience, but it is made up of parts of me, the soft, wet, dark pieces. Since I am in control, I can sometimes cover this audience in a tarp so they can’t see me.

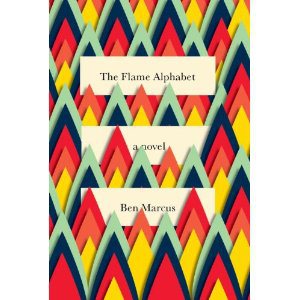

UFR: In your newest novel, The Flame Alphabet, “families are being torn apart by an epidemic of lethal children’s speech.” What caused you to pursue this idea? How did the novel start? What sparked its creation?

Marcus: I never really believed in the sticks and stones saying that names can never hurt us. How else can the pain be explained? I like to pump air into things and then examine their shape. This novel takes a true story and drugs it to make it stronger.

UFR: About The Flame Alphabet, you say in Harper’s that “If language is poisonous in The Flame Alphabet, maybe in our world it is not poisonous enough. Or maybe it is not so easy to weaponize, and that’s part of what one tries to do with fiction. It’s difficult to arm a narrative with agents of derangement, something so vital it gets in our blood, like a drug.” Can you talk about that idea a little more? What do you mean, exactly, when you say “weaponize?” In fiction, why is it important to “arm a narrative?”

Marcus: It’s not important, I’m sure. It’s just something I wanted to do. I had been writing work that failed to hold my attention, and I wasn’t feeling very patient. I felt desperate and lonely. Not people lonely. Writing lonely. So I decided to try to hold myself hostage to a narrative that felt too troubling to ignore.

UFR: Your previous books, The Age of Wire and String, The Father Costume and Notable American Women made big splashes, and have all been wildly idiosyncratic. Can you talk a little bit about your writing evolution? What are you concerned with now that you weren’t thinking about back in say, 1998? (Or are you still concerned with the same sorts of things?)

Marcus: No one wanted to interview me then, so I never had to say or explain any of this. Over time I think I have gotten to the bottom of certain fascinations. Suddenly they horrify me. It seems natural to suffer countless breakups with one’s own ideas. With other interests I’ve realized they were shields or obstacles to something more important. What’s constant, maybe, is the way I want to feel when I’m working, a kind of compulsion and anxiety, although this sadly does not mean that what I’m working on will be any good.

UFR: You’re famous for being a champion of experimental fiction. I’m not asking you to define the time, or genre, but I’m asking a question beyond that, I think. It seems that experimental writing is so exciting, so bracing and searing, and even deeply full of heart. How do you achieve such writing? Is experimental writing something you can practice, or is an innate style?

Marcus: I really do not know.

UFR: A question I love to ask: What writers make you jealous? What on your bookshelf can you go to and read again and again? That’s to say, are there any books you read and say to yourself, I wish that was mine.

Marcus: David Markson, Jane Bowles, Sam Lipsyte, Dostoevsky, Kafka, Ishiguro, Flannery O’Connor. But I don’t feel jealous towards them. Just grateful.

UFR: What are you currently reading?

Marcus: U and I by Nicholson Baker. New books by Vincent Standley and Gary Lutz. The new Mark Leyner novel.

UFR: If you were to talk to someone who didn’t know what writing was, had never even heard of the stuff, what books would you recommend to make him or her understand?

Marcus: It would seem socially impolite to proselytize about literature to innocent people. I talk to people like this all the time. Most people in the world, in fact, are like this, which is just fine. I would try to find a common interest in the conversation. Or, if they were attractive, I would propose intercourse.

UFR: Why do books matter? Why does fiction matter? Finally, why does writing matter?

Loved this interview!! I love the vision he has of himself sliding across water! And that he would propose intercourse, bypassing conversation about writing!! I haven’t read his work, but am now going to buy a copy and start reading!!! Thank you, UFR, for another outstanding interview!!!

Everything Meg said, yes. Well done.

Love the pictures. We have a connection of some sort: recently, I submitted to a magazine and when I received my rejection, the editor called me “Ben”. When I inquired (thinking that I had got the wrong letter), it turned out that she’d mistaken me for you. So — I suppose we share a rejection. We’re both rejects. There’s a tale in that observation but I won’t write it. Cheerio from Berlin.

PS. she’d rejected my story, to be sure, but she confirmed that she’d thought of “Ben Marcus” when writing to me. Easy mistake given our pre/surname twin suture.