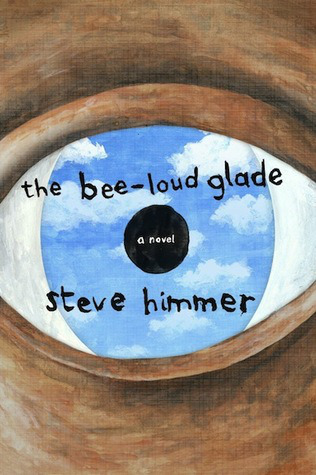

In Steve Himmer’s debut novel The Bee-Loud Glade (Atticus Books),

Finch, a down-and-out corporate blogger whose life is spiraling,

receives an email from Mr. Crane, a billionaire in search of someone to

employ as a decorative hermit on his enormous property. Finch accepts

the job and what ensues is a rich, funny, “postmodern pastoral,” that

explores – among many others topics – that messy intersection of

humanity and nature, humankind’s efforts at preserving nature, and

America’s preoccupation with a certain brand of self-reliance.

In Steve Himmer’s debut novel The Bee-Loud Glade (Atticus Books),

Finch, a down-and-out corporate blogger whose life is spiraling,

receives an email from Mr. Crane, a billionaire in search of someone to

employ as a decorative hermit on his enormous property. Finch accepts

the job and what ensues is a rich, funny, “postmodern pastoral,” that

explores – among many others topics – that messy intersection of

humanity and nature, humankind’s efforts at preserving nature, and

America’s preoccupation with a certain brand of self-reliance.

Along with his writing, Steve Himmer teaches at Emerson college and edits the literary journal Necessary Fiction. Contributor Ross McMeekin had the opportunity to speak with him over email about his novel, life, and writing process.

***

Ross McMeekin: I gather you’re a bit of a naturalist. What are some of your regular haunts?

Steve Himmer: I don’t get to spend nearly as much time in the woods or in other wild places as I’ve been able to at other times in my life, but it is very important to me. Just knowing the ocean is nearby—I live within walking distance of water—makes a big difference, and it’s the same with the woods. These days, most of my exploring happens with my daughter in the salt marsh by our home. There’s an active osprey nest and plenty of birds and smaller animals to spot, and at night coyotes and foxes and opossums are out. There are also fishers, which I’ve heard shrieking in the middle of the night but haven’t managed to see yet, though I hope to do some night spotting for a story I’m planning to write.

RM: While reading The Bee-Loud Glade, I was taking care of my newborn baby girl. With her crazy schedule, I often found myself watching the PBS show Alone in the Wilderness at weird times at night, which provided an interesting counterpoint to your novel. Similar to Finch, the guy on the show is “alone,” yet a plane drops off supplies on a regular basis and everything is being filmed. I’m curious what books, films, etc. informed and inspired this novel.

SH: I love that show—it’s one I watched with my own newborn, when she was one, and when colic kept her (and her parents) awake at all hours. It’s a great example of the mythic American figure of the wilderness loner, isn’t it? It was definitely an influence on the book, along with Thoreau, of course, and all the reading I did about hermits like Frederick Buechner’s novels Godric and Brendan. Isabel Colgate has a little book called A Pelican In The Wilderness that’s a kind of notebook of hermit lore and literature, and there’s a magnificent website at Hermitary.com I just can’t thank enough. Some of those, like the Colgate, I read as research specifically, but others like Thoreau and Yeats I’d read years earlier when all this was just bubbling away. And I have to mention the BBC show Worst Jobs In History because that’s where I learned “ornamental hermit” had once been a job and it sparked the idea for the novel.

The degree to which other books, films, music, and so on found their way into the story is important to me. It’s a bit like Finch’s own conflicted quest for self-suffiency, isn’t? As a writer I’m trying to make something new, on my own, yet I’m wholly dependent on the work of others and my experience with their work to give me something to work with myself. Even when trying to write about a mind getting away from the world of TV and websites I had no choice but to do so with a mind steeped—and steeping—in them.

RM: At times I found myself wishing I had Finch’s job, or a perhaps less controlled version of it. I’m interested in hermetic self-reliance as a commodity – both from how it’s presented in your novel as well as in shows like Alone in the Wilderness and books like Walden, Into the Wild, and even a childhood favorite of mine, Hatchet. I love that stuff. How do you think people like me come to idealize this idea of loneliness and self-reliance? I’m curious what you think about our culture’s drive towards this sort of self-sufficiency.

SH: Sometimes Finch’s job appeals to me, too. But I don’t know, I have some ideas about self-sufficiency but I hope the novel avoids making any kind of prescriptive gesture about what someone should or shouldn’t do. Finch’s own situation certainly is more complicated than any philosophy could account. I think people idealize it, in large part, because they don’t have to live it, so it seems a romantic escape from the often hectic lives we do live. It’s a lot like manual labor or farming or any number of other things that have romantic qualities attached to them from a distance but are painful and frustrating and hard to actually do. Not that there isn’t nobility or accomplishment in them, but as the British writer Jeffrey Bernard said, “As if there was something romantic and glamorous about hard work … if there was something romantic about it, the Duke of Westminster would be digging his own fucking garden, wouldn’t he?” I got that from Tom Hodgkinson’s book How To Be Idle—another big influence on my novel—and had it hanging in big print on my office wall for a while. And I think there are checks and balances: we might work more often alone, but find connections in other ways. When I’m huddled at home alone writing fiction I’m also bantering away on Twitter, being social. I idealize loneliness and solitude as much as anyone, probably more so, but mostly I suspect I can get away with it because I’m not truly alone. Nothing close to it.

RM: I have heard various arguments about using nature as a metaphor in writing – whether it is a good, ethical, etc. I’d love to hear your take on the subject and how you navigated it in this novel.

SH: I was very conscious of it. Maybe too much so because as a writer I do tend to get bogged in “ideas,” sometimes to the detriment of the writing itself. I read lots of environmental history and theory anyway, not as research for the novel, but I had to shut most of it out when I sat down to write. But I was very deliberately trying to avoid any claim to writing about a “real” place, a real landscape or nature. It’s as much artifice as nature in a number of ways, and while in the story that occurs in exaggerated ways it’s not so different from the world we live in. Every bit of ground we encounter is already wrapped up in webs of science or communications or folklore or literature or pollution, nothing’s “untouched,” and as a writer I want to explore. I’m not the least bit interested in idealizing a nature that doesn’t exist, but would much rather read and write about the confusions and discoveries that are only possible in the mediated quasi-natural world we actually live in, for better or worse. So I hope readers are constantly off guard, a bit, as to what’s natural and what isn’t and as to how literally to take the story. Some writers try to hide the construction of a text just as they try to make their setting seem “real,” but neither of those interests me much.

RM: I’m an aquarium enthusiast and recently bought a pair of captive-bred clown fish. They’re pissing me off because they refuse to nest with any of my anemones, like their counterparts do in the wild. Presumably this is because they no longer need to, as they are safe in my aquarium. So I laughed when reading the passage where Finch attempts to help Jerome the Lion roar more like a lion and ends up only helping him sound like Finch trying to be a lion. It seemed emblematic of so many aspects of the novel, in which the characters try and fail to accurately represent nature in its less manipulated form. I’m curious how your opinion about some of our world’s more misguided efforts towards preservation, both now and historically.

SH: I’m not opposed to preservation, not at all, but it does get complicated, doesn’t it? At what point does an animal preserved through generations of laboratory manipulation stop being that animal and become something else? I’m really interested right now in invasive species and “wild” animals encroaching on urban areas. I’ve been thinking about how raccoons, among other species, have been adapting so well to city life that they’re becoming biologically or behaviorally distinct from their country kin. It’s not through anything we’re doing, not like in a lab, but just by living near us and taking advantage. That give and take of interspecies relationship, whether with raccoons and bears or purple loosestrife or snakeheads, is so rich to me with stories and provocative ideas. Some of it’s horribly destructive, of course, but much of it’s not. So Finch and Jerome, the man teaching the lion while the lion teaches the man, is maybe indicative of that: a give-and-take between species, both changing in response to one another and becoming something other than what they were. Not, hopefully, to the extent that Jerome loses his lion-ness (and suddenly I’ve reminded myself of Russell Hoban’s wonderful novel The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz) or Finch his human-ness. I’d hate to live in a world where lions didn’t still try to eat us when they had the chance, which isn’t to say I want to be eaten.

RM: I’m wondering about the subplot and character arc of Mr. Crane, which I thought were very well done. I found myself wanting to know more about him, but by the end, I was fine with not knowing as much as perhaps I would have liked. Was there ever a time in the novel draft where you wrote out exactly what happened to him? Also, how did you go about making the decision of how much to tell and how much to leave out?

SH: I never wrote any of that out but I did make notes. I have an idea of what happened to him, or at least I know how he gets himself into trouble. But I never intended to make that part of the story. Partly because Finch lives in a bubble and tries really, really hard to stay in that bubble, so there’s little reason he’d tried to know more. But also because I think of him as a character moving through a world filled with networks of power and influence and wealth behind the scenes, lots of moving parts all the time, that have a huge impact on his life without him really knowing. Which is maybe how I think all of us live. Someone like Finch—or like me—wouldn’t have access to the inner circle, so to speak, any more than the rest of us do. Process-wise, it’s something I “borrowed” from William Gaddis, especially his novel Carpenter’s Gothic, in which there are parts of the story happening always off-stage—often big parts, politics and war and the kinds of things you’d expect the novel to be about. I love it when stories do that, right back to Beowulf: one of my absolute favorite moments in literature is after Beowulf vanquishes Grendel then his mother (spoiler alert!) and the poet tells us, “And then Beowulf was a great king for fifty years,” before getting to the dragon. It’s wonderful, to direct the reader’s attention away from seems to matter most and seems most dramatic, what they’d expect to read about, and say, “No, you’re going to read about this instead.”

RM: How and when did you decide to structure the novel with chapters switching between the present and the past? Was it planned that way, or did you arrive at the decision later on in the process?

SH: It came fairly late, I guess. I’d written just about a full draft without the parallel structure. Both stories were there but the whole book was chronological: the first half Finch’s half, the second his present. But something was missing, it needed another kind of momentum, and I’d read Per Petterson’s Out Stealing Horses and said, “Aha!” So I read his novel a couple of times, really paying attention to the parallel structure he used and how he transitioned from one thread to the other, and tried make it my own.

RM: What are you working on now?

SH: I’ve got a novel that’s finished, full of the invasive species and bears and so on I mentioned before. It’s a wilderness adventure and a monster story and a bit supernatural, the story of a contractor who moves to a small forest town to build some houses and gets caught up in things bigger than himself. It’s a lot of stone walls and power lines, the different kinds of networks through which we make a place, and characters who are homesick for places they never knew while others are missing the place they’ve always lived in because it’s changed so much. So, you know, more lonely people like in The Bee-Loud Glade but they’re more social this time. And at more risk.

And right now I’m working on the first draft of a new novel, meant to be something different because I realized everything I’ve written for several years has been about characters staying put and having their experiences of a place over time lead to a story. So this time I’m intentionally keeping characters in motion—specifically a couple of bureaucrats sent on an errand to the Arctic—so the setting is constantly changing and I have to respond to it differently, almost like a spy novel at times. It’s fun so far. A very different feel from writing The Bee-Loud Glade or other projects I worked on, and hopefully that will work for some readers. Or first for a publisher, I suppose.