Michael Kimball is the author of four books, including Dear Everybody and, most recently, Us. His work has been on NPR’s All Things Considered and in Vice, as well as The Guardian, Prairie Schooner, and New York Tyrant. His books have been translated into a dozen languages—including Italian, Spanish, German, Chinese, Korean, and Greek. He is also responsible for Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (on a postcard), a couple of documentaries, the 510 Readings, and the conceptual pseudonym Andy Devine.

***

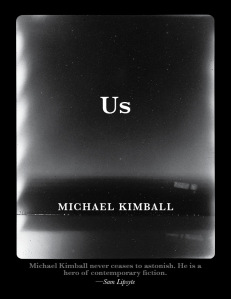

UFR: Your latest novel, Us, has been getting a ton of buzz lately. Published by Tyrant Books, it was originally released in the UK in 2005, and there it was titled How Much of Us There Was. How would you explain the book?

Kimball: When I explain the book, I only try to explain part of it. I tell people that it’s a novel about an older couple during the last days of their long, loving marriage. I tell people that the novel is about grief and the extreme behavior that grief can lead to, but only because it is also about very much about love.

UFR: In the two editions, has anything changed besides its title? What was it like revisiting your work and preparing it for re-release?

Kimball: I didn’t know if I was going to even look at the text of the novel. I knew that if I looked, then I would want to make changes. I asked a few writer friends what they would do and everybody advised me not to change anything, to let it be what it has always been. But, ultimately, I couldn’t not look and the changes were obvious to me when I did. I changed the title, shortened all the chapter titles, cut a lot of little words at the beginnings and the ends of sentences, and moved the former last chapter to the end of Part Three. I felt as if I could give the novel a slightly deeper tone and all of those changes were in service of that. Having the chance to revise the novel like that was incredibly satisfying. I wish that I had the chance to do that with each of my books.

UFR: Even though your work is stunning, the lives of your characters are filled with different kinds of grief. Why is it that you write stories through a lens of sadness and reckoning?

Kimball: I’ve tried to write about other things and from different perspectives, but no matter where I start, I head toward the dark and the difficult. I feel as if it doesn’t matter if I’m not writing about something dark and difficult – and trying to do it in a different way. I recently finished a new novel that may be the end to that trajectory, though, a thing called Big Ray that feels like a culmination of 15 years of writing – pulling together different things that I was doing in Us, in Dear Everybody, and in the postcard life story project. I don’t know what is next, but feel as if something different may be waiting for me.

UFR: You recently edited the latest edition of The Love Letter Collection, called As If We Are Not Ourselves. In your letter from the editor, you write, “There is something beautiful about glimpsing the love between two people I do not know.” Writers often speak of knowing their characters, or of getting to know them. Do you feel like you know, say, Jonathon Bender in Dear Everybody, or the characters of Us? In writing, did you get to know them over time? As the creator of these characters, are you doing more than glimpsing, or is a glimpse of their lives the best you can hope for?

Kimball: I don’t quite feel as if I know the characters in my books like I know people in my life, not even the characters that are based on real people. To use the vocabulary in play, I feel as if I just have glimpses of them. What I do become familiar with is a character’s way of talking and thinking. The voice that comes from that is difficult for me to shake after I finish writing a book.

UFR: As a writer, why are you drawn to the world of fiction?

Kimball: I started out as a poet, but I wasn’t particularly good at it. At best, I was just writing these clever little funny things. At the time, I couldn’t figure out what else to do with poems. I was even worse when I started writing fiction, but writing sentences and working with story felt right to me. I was able to find a voice and see more possibilities in fiction.

UFR: Do you think fiction helps us better understand our lives? If so, how?

Kimball: Years ago, I wouldn’t have said that fiction helps us better understand our lives, but now I would. Now I do. I never expected something like that to happen with fiction, but I’ve found new ways to think through writing fiction. I’ve found things that I didn’t know I thought. The last year, especially, working on Big Ray, has been transformative.

UFR: For you, what does writing accomplish?

Kimball: When the writing is going really well, there can be a kind of euphoria that fills me and that I carry with me for months. Right now, I’m coming down from a many-month writing high and kind of looking for the next fix.

UFR: What’s so striking about Us, and even Dear Everybody, I think, is that each sentence really counts. How do you get your work to that level? What does your revision process look like?

Kimball: After I get some material to work with, I’m very conscious of paring things down. I’m trying to tell as much story and convey as much feeling as possible with as few words as possible. I’m trying to make each sentence do multiple things —advance story, convey emotion, provide a certain voice, build character, replicate a certain syntax, make acoustical resonances, etc. In doing so, I’m making some assumptions about what a reader brings to reading a book when I do this. I feel as if there are a lot of things that fiction writers don’t need to describe anymore. So I get to that pared down state by drafting material and then distilling it, getting rid of everything that doesn’t seem absolutely necessary. This takes a different form in Us (where feeling is the thing that is compressed) than Dear Everybody (where it is story that is compressed). Also, I’m trying to write the kind of thing that I would most like to read. I want a kind of intensity, also a certain narrative speed, two things that compression can make happen.

UFR: When did you first realize you loved to write? When did you consider it a vocation?

Kimball: I always liked to read when I was growing up, but I never really liked writing. I still remember this book that I was supposed to make, a class assignment when I was in 4th grade. I never did it. I didn’t start writing in any creative way until college, after a girlfriend dumped me, and those were just some really bad poems. It probably wasn’t until I published my first novel that I felt as if writing could be a vocation, but I had been doing it for years by then.

UFR: What are you currently reading? How is it?

Kimball: I just started Jon McGregor’s So Many Ways to Begin, which is wonderful so far. And I just finished Michael Bible’s Simple Machines, which is a new piece of genius from Publishing Genius, their Awesome Machine imprint.

UFR: If you were to talk to someone who didn’t know what writing was, had never even heard of the stuff, what book would you suggest to make him or her understand?

Kimball: I love this question, but I don’t know how to answer it. Oh, wait, I thought the question was asking for an explanation of what writing is. I was going to try to make something up about “writing behavior.” But a book, one book, I would just pull it off my shelves, and the first thing I just looked at is Grace Krilanovich’s The Orange Eats Creeps, which I think is a good choice, makes it clear that writing, real writing, is something that is rendered.

More interviews at Used Furniture.