(Photo © Joni Kabana)

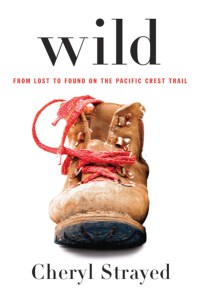

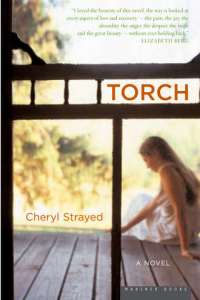

Cheryl Strayed is the author of three books: Wild, a memoir (Knopf, 2012), Tiny Beautiful Things, a selection of her “Dear Sugar” columns from The Rumpus (forthcoming from Vintage, July 2012), and Torch, a novel (Houghton Mifflin, 2006). Wild has been optioned for film by Pacific Standard. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the Washington Post Magazine, Vogue, Allure, Self, The Missouri Review, Creative Nonfiction, The Sun and elsewhere. She holds an MFA in fiction writing from Syracuse University and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Minnesota. She’s a founding member of VIDA: Women In Literary Arts, and serves on their board of directors. More at http://www.cherylstrayed.com/.

***

UFR: Your work is diverse – fiction, nonfiction, memoir, advice. Do you have a favorite genre as a writer? As a reader?

Cheryl Strayed: As a reader, I’m interested in good writing in all its forms. Reading is my favorite thing to do. When the writing is good, I’ll read anything. My fantasy vacation would be spent reading an enormous stack of books and magazines. As a writer, the different genres feel very much the same to me. I don’t mean to say that they are the same. I mean that the visceral experience of the writing itself feels the same when I’m caught up in it, whether it be fiction, memoir, personal essays, or my “Dear Sugar” columns. I love to lose myself in the sentences.

UFR: The subject of truth in literary nonfiction fascinates me. Stephen Elliott has said that truth is a “liquid thing.” Do you agree? Is there such a thing as objective truth? Are honesty and truth the same thing?

Strayed: I think those of us who write literary nonfiction are in the midst of a fascinating time right now. A lot of us are writing about what the genre means and because we don’t all agree, I think some feel that the genre is under siege, but I don’t think so. I believe the conversation that’s happening can only help us think more deeply about what we’re doing, about what it means to write literary nonfiction. One of the challenges is that we’re still developing a shared language that expresses exactly what we mean about how subjective truth works on the page. When we say the word truth, do we mean big truth or little truth, collective truth or private truth, truth as we remember it or truth as we researched it? When you tell me Stephen Elliott said truth is a “liquid thing” and ask if I agree, I don’t honestly know. My answer is: it depends on what he means by liquid. And I think that’s what might be so complex about talking about the genre. It takes some explaining.

I recently had an essay in Post Road and in it I say the line for me between fiction and nonfiction is clear—that in one you can write whatever you want and in the other you can write whatever you want without making shit up. That’s my guide. In my nonfiction, I don’t make shit up, but that’s different from saying I got everything right from an objectively true standpoint. Did I misremember the name of a river? Was I harder or easier on someone than I should have been? Did the conversation I reconstructed from memory unfold in the way I recall? I take those questions very seriously. I make every attempt to be accurate and fair in my nonfiction writing. But the story I’m telling is my own, which means it’s a story that’s altered, expanded, and constrained by my very particular consciousness.

UFR: When you write about real people, there is always the chance that they won’t like how you’ve depicted them, won’t agree with your version of the story. Do you worry about that? Do you ever show people ahead of time what you’ve written about them?

Strayed: I worry about that quite a lot. It’s a fine balance. You can’t let people stop you from writing your truth, but I think it’s important to consider them too. There are people in my memoir Wild about whom I could have written far more. I scaled things back because I didn’t want to violate their privacy or hurt their feelings. None of the stuff I left out prevented me from telling the story I wanted to tell, but it would be a slightly different story if I wrote without concern for the feelings of others.

I don’t share my work with people I’ve written about ahead of time—or if I do, it’s not usually with the purpose of getting permission. The one exception is when I write about my husband in my “Dear Sugar” columns. I talk with him about what I want to write and then show it to him before it’s published. He’s been only supportive of me, even when something I’ve written makes him squirm. So far only one person has become angry about something I wrote, and I hadn’t even written about her, but rather someone she’s close to. The fact is, she would have been angry with me about writing anything. When making decisions about how much to take someone’s feelings into consideration, it’s important to consider the source. Are you getting hell from someone who has a valid concern or from someone who essentially believes you shouldn’t write? One cannot allow people like the latter to guide the boat.

Some really good things have come about because I wrote about others too. I think we forget that when we get so focused on how anxious-making it is to write about those in our lives. My brother, Leif, appears in Wild in some of the most important scenes. I gave him the book last fall and felt nervous about it. He’s presented complexly in the book, just as he’s a complex man in actual life. I love him deeply and I write about that love in Wild, but I also have some hard things to say about him, so when he called me to tell me how much he loved the book, I was terribly relieved. We then had one of the most profound conversations I’ve ever had with anyone. The book had opened him up, he told me. We shared things we’d never shared before. He said it wasn’t always easy for him to read what I wrote about him, that sometimes he felt mad or he disagreed with a point, but then he’d read on and forgive me and understand. That conversation was a gift that my book gave me.

UFR: The story behind Wild – your 3-month solo hike over 1100 miles of the Pacific Crest trail – happened when you were 26. I’m assuming it’s been a book inside you all this time. What made you finally write it now?

Strayed: It wasn’t a book inside me all this time. I didn’t intend to write a book about my hike. What happened is in 2008 I got this idea to publish a collection of my personal essays and I thought I’d round out the collection with an essay about my PCT journey. I began writing it and soon realized I had a bigger story to tell.

UFR: One of my favorite lines in Wild is this one: “Of all the things I’d been skeptical about, I didn’t feel skeptical about this: the wilderness had a clarity that included me.” I loved that sentence because throughout the book, I felt the interplay – the sort of dance that occurred between the wild that was within you (made of loss and grief and youth and anger) and the wild that surrounded you on the trail. Neither one was tamable, both had to be, in the end, respected, accepted. Loved. Can you talk about that, how you felt about it then, how you feel about it now?

Strayed: I think the wild places are important to our collective humanity and also to our individual souls. It’s where I feel the most gathered and calm. It’s where my children go into this wonderfully creative and constructive mode. I’ve never been in the wilderness and thought I was in the wrong place—even when, as happens in Wild, I am in fact utterly lost. Its beauty is like a cure. I thought that back in 1995 when I hiked the PCT and I think that still.

UFR: Hiking the PCT was life-altering. I imagine the process of writing it all out, retracing your steps, learning what happened to some of the people you met has been its own sort of life-changing journey. On the PCT you were, as you say, lost and found. What has the experience of writing about it been like?

Strayed: It’s been amazing. You’re right that writing the book was a journey all its own. Every book is, but perhaps a memoir is more intense because you have to entirely gut yourself. I learned so much about my hike on the PCT by writing about it. I had to push myself to go deeper, to reflect on what the hike meant to me, to sift through the endless days of walking and make sense of them in narrative form. The day I finished Wild I felt so lucky to have had that opportunity to dig so deep. I knew that no matter what happened with the book, in writing it I had changed.

UFR: I love in Wild how you talk about your incessant curiosity as a child, your constant questioning of your mother who couldn’t understand why you wanted to know so much, and the questions you were nonetheless left with once she was gone. My own mother is very private, but readingTorch andWild made me realize that I can’t wait for her to tell me her story. I have to ask her about it… and keep asking. I regret all the years I didn’t ask, wonder (painfully) about my reasons. Now that you have your own children, how does what you’ve been through–the loss of your mother so young, the questions you were left with, the stories you didn’t get to hear–affect the way you communicate with your son and daughter?

Strayed: I love to talk, to ask questions, to share stories. I share that side of myself with my children all the time—mostly because I don’t see it as a “side.” It’s just who I am. I’ve been open with my children about my life. They know my mother died young of cancer and they know how difficult and sad that was for me. They know I didn’t have a father who was a positive presence in my life. They ask about both of them and I tell them everything I can. They know I was married to someone else before I married their dad. They aren’t alarmed by this. It’s only in creating silences around subjects that we make them strange. Some people use silence to make their whole lives taboo.

UFR: What do you think is the most important lesson for you to impart on your children? What was the most important thing your mother taught you?

Strayed: Kindness is the most important thing my mother taught me and it’s the most important thing I teach my kids too. I want them to achieve all their dreams, but my dream for them is that they will always be kind to others. That matters more than anything. Mean people are miserable people. When you’re kind you always have love in your life.

UFR: So, your hugely anticipated memoir is finally out (yay!), you’ve been outed as Sugar, and the Sugar book, Tiny Beautiful Things, will be released in July. How do you feel? What’s next for you?

Strayed: It feels great! It really seemed like time to do [the Sugar reveal]. So many people were figuring it out anyway. It was becoming a burden to keep the secret. The column feels the same to me, aside from the fact that I’ve not been able to write it much lately. I’m incredibly busy with getting Wild and Tiny Beautiful Things out in the world. What’s next for me is September. That’s when I think I might actually be able to collapse on my couch and take the vacation I mentioned above—the one during which I simply sit and read a stack of books and magazines. If there is a god that grants wishes to over-worked writers, that’s what’s next for me.

UFR: Finally, who are your favorite authors and what are you reading right now?

Strayed: Alice Munro is my favorite writer. I’ve never read anything by her that didn’t amaze me. Mary Gaitskill is another writer I admire tremendously, as is Mary Karr. I re-read her memoir Lit a few months ago and was reminded all over again what a kick-ass writer she is. Right now I’m reading Philip Connors’ memoir Fire Season, about his experiences working as a wilderness lookout. It’s filling me with a profound longing for the wild and silent places.

***

Judy Clement Wall conducted this interview on behalf of UFR. Judy’s short stories and essays have been published in numerous literary journals and websites such as The Rumpus, Lifebyme, Smith Magazine and Beyond The Margins. You can find out more about her and her work at Zebrasounds.net.

More interviews at Used Furniture.

This is an amazing interview… perfectly compliments a book I am anxiously waiting to read.

The questions and answers here are far more involved then most interviews… so glad I stopped by.