Photo credit: B. Frayn Masters

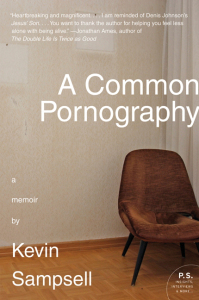

Kevin Sampsell is an editor (Portland Noir and other books), publisher (Future Tense Press), bookstore employee (Powell’s Books), and author. His latest book is A Common Pornography. He lives in Portland, Oregon. www.kevinsampsell.com

***

M Thompson first met Kevin through his publishing imprint, Future Tense Press. He had just moved to Seattle and was working at a bookstore. One evening, while exploring local presses, he came across the scrawled strangeness of Future Tense’s website and instantly reached out to the books on the shelves. There is a lean and manic energy to Future Tense that M finds immensely satisfying. With each book that they release, he feels he’s in good company – like arriving at a house party and hearing Wire’s Pink Flag being played from the basement. Since their correspondence began, M has grown to know Kevin and Kevin’s writing and the writing that he releases. He counts himself as a true supporter and a happy fan.

Thompson: Let’s begin with your publishing imprint, Future Tense Press. Fill us in on its origins and where it stands now.

Sampsell: I started Future Tense in 1990 when I was living in Spokane. I didn’t know it would grow into a press where I’d be publishing books by a bunch of different people. It was initially just something to put on my own scrappy little typewritten chapbooks that I would make at Kinko’s. Now, 21 years and a bunch of technology later, I’m getting published by other presses and I’ve let my press become a stage for new and exciting writers that I love, people I think should have a book out there but don’t yet. I like to think of Future Tense as a kind of launch pad or even a stepping-stone for these talents, to help them get noticed. I’m kind of a farm league.

Thompson: You’ve mentioned in previous interviews that you’re entirely content to keep Future Tense operating at an independent, “farm league,” level. I’m sure there are practical reasons for this, but I sense a deep-felt appreciation for the small press world as well. What is it about independent publishing that inspires you to participate and, more importantly, continue that participation?

Sampsell: Part of this thinking is that I just want to maintain a balance between what I do for others and what I’m doing for myself. If I wanted to make Future Tense a bigger press and publish twenty books a year, I would probably never have time to write my own work or even read other books. So I publish three or four books a year and have time to write my own stuff. I also have to admit to you that I hate reading manuscripts. But I love to read real books published by all sorts of presses. So I need time to do that too. Reading books is just as important to me as publishing and writing them.

Thompson: I’m curious to what degree all of your editing and publishing work influences your own writing. Do you feel you’re a better writer because you’re also a publisher? Or perhaps a different writer?

Sampsell: I think it has helped my writing for sure. I didn’t go to college for long at all, so this has been my education. I learn as I go.

Thompson: Do you find yourself acting as your own editor while writing? It seems that being a writer as well as an editor could make you an extraordinary literary machine or split your brain in half.

Sampsell: That’s a funny way to think about it. I do sometimes argue with myself. And I think I do write slowly because I’m thinking as an editor at the same time. Not content-wise, but grammar-wise. I can get really hung up on a sentence or how to end something and just sit there for two hours working on the same few words. And the funny thing is—the point of my editing is to make my writing seem as natural as possible. I do have a couple of good reader friends I send stories or chapters to when I get them done. They help me clean up anything I missed.

Thompson: The stories that you write are often quite short in nature. Many of the books that you publish (Prantha Lohr’s Ventriloquism comes to mind) are highly condensed as well. What are your thoughts on short fiction, or microfiction, or flash fiction? It’s a writing style that has certainly picked up speed in recent years. Are you excited about the current state of the short story, or the short short story?

Sampsell: I love short stories but I also fluctuate sometimes and want to read either longer work or nonfiction. But overall, I think the length of a story is not that important. It’s the sensation that a reader can get from a text, whether it’s a haiku, a prose poem, a flash fiction, or your standard twenty-page MFA-workshopped story. A lot of the fiction that I write and publish is on the flash side of that group. One of the reasons behind that is simply the size of the books I publish. The fiction chapbook, which I love, and I think readers love too, because they can get a quick introduction to a writer they may not know about. They get a taste and then hopefully they want more. I’m not a drug dealer, I’m a story dealer.

Thompson: As a story dealer, and a book dealer, do books as objects matter to you? Is the physical presence of a book – its design, its typeface, and its paper – an integral part of the combined charge you receive from reading it?

Sampsell: If a story is great or if a line in a poem is great, it doesn’t really matter how you’re reading it, in a book or on a computer, you’re still going to get a charge out of it. But of course, I think the physical book is the ultimate package to contain any writing. I like to have books around. If I’m talking about a book, at home or at Powell’s, it makes all the difference in the world that I can actually hand it to the person I’m talking to. I think ebooks have their place in modern culture, but yes — real books are where it’s at.

Thompson: Your most recent release, A Common Pornography, is out now from Harper. It’s a fascinating exploration of memory, composed of highly personal vignettes, and billed as a memoir. Yet, earlier versions of the book, or parts of the book, have been released as fiction. While assembling ACP, was there a moment where it suddenly dawned on you, “Oh. These aren’t imagined stories. I’m writing about myself”?

Sampsell: The first version of the ACP book was always called memoir. I think I have said in interviews though that the genesis of the book was a story of snapshot vignettes that I wrote a long time ago and then realized, Hey—these are all true stories! But more than that, I realized that they were memories. That’s why I called it a “memory experiment”— to see how much my memory could remember.

So yeah, early on, I did have an odd kind of a-ha moment because I was so used to writing stories that were more obviously fiction. I guess you could say that ACP started off as an accident.

Thompson: Did that experience change your understanding of the relationship between fiction and non-fiction?

Sampsell: Well, I don’t want to sound defensive but I’m definitely not one of those writers who bend their non-fiction every which way. I don’t believe in speculating too much in non-fiction or filling in blank spots that I can’t remember.

On the flipside to that, I will say that fiction as a genre lends itself to be messed around with and manipulated in ways that non-fiction can’t be. I’m writing a novel right now and I’d say that more than half of it is probably made up of true stories. But of course, fiction readers aren’t going to freak out and say, Hey—this isn’t fiction! That writer lied to us!

Thompson: Tell us more about the new novel. Does it have a name?

Sampsell: Yes. It’s called, This is Between Us and I’m hoping to have it done by the end of the year. I’m really excited about it. It’s kind of like ACP, in that it is written in very short chapters. A bunch of little scenes, bits and pieces, ups and downs, of a modern relationship in Portland, Oregon.

Thompson: And what about Future Tense? Any new projects?

Sampsell: We have some great stuff coming up. Shane Allison’s I Remember (his own updated version of the Joe Brainard classic) will be out this fall and Chloe Caldwell’s book of essays is coming out in spring. Also, we are working on putting out some ebook versions of some of our newer books. It’ll be an interesting new world to investigate. Also—we’re going to be doing a Kickstarter campaign soon to help us cover the costs of these projects. We’ve never really asked our readers for help in this way, but we need to do it and I hope people respond to it.

Thompson: Okay. Last question. And, as a bookseller, I feel I have to ask. What are you reading right now?

Sampsell: I’m reading a lot of stuff, including this big graphic novel called, Essex County by Jeff Lemire. It’s really great, sad, and beautiful. I’ve been reading more poetry this past year while working on this novel. It seems to inspire me more to write sometimes. For example, I love this little book by Gregory Sherl called, I Have Touched You and also Emily Kendal Frey’s last couple of collections. There are lines in those poems that make my head explode with ideas. Plus, I’ve read a lot of stuff by Leonard Michaels this past year after I discovered how great he is.

***

M Thompson was born in northern Michigan and now lives in Seattle. His fiction, book reviews, and interviews have appeared in places like Unsaid, Everyday Genius, The Collagist, Monkeybicycle, jmww, and Spork, among others. He is concerned primarily with fiction writing and running long distances. www.m-thompson.net

[…] Furniture Review has a great interview with my friend and publisher: I Learn As I Go: A Conversation with Kevin Sampsell. In it, he answers a good amount of questions about Future Tense Press, and his new novel, […]